Welcome to the online writing portfolio of Debra Leong.

Creative Writing

♣ Dream Chronicles (2009)

♣ The Victim (2006)

♣ Cats (2003)

♣ Commonwealth Essay entry (2003)

Art, Music and Film Writing

♣ Nathalie Djurberg (2009)

♣ Oranges and Sardines - Conversations on Abstract Painting (2009)

♣ The Age of Imagination: Japanese Art, 1615-1868, from the Price Collection – Encore (2009)

♣ Italian Film - The Seduction of Mimi (2007)

♣ Opera - Armide (2006)

Academic Writing

♣ Globalization and Women's Political Power (2006)

Saturday, August 15, 2009

Thursday, August 13, 2009

Opera - Armide

Nicolas Poussin, Rinaldo and Armida

The story of Rinaldo and Armide is, to say the least, an intriguing one. It interweaves tales of conquest with moments of passion, blurring the lines between love and hate. It first appeared in the form of a 16th century romance epic, the Gerusalemme Liberata, by Torquato Tasso. Since then, there have been numerous reincarnations of the tale in different operas throughout the ages. This essay shall focus on two specific operas in the Baroque period, namely Jean-Baptiste Lully’s Armide and George Frederic Handel’s Rinaldo. I will attempt to compare and contrast these two productions, concentrating on elements in their librettos and musical dramatic techniques.

The librettos of these two operas share some common traits. Both of them exalt the value of war and glory over love. War is seen as a manly, honorable activity; a means of achieving one’s goals through fair play. In Giacomo Rossi’s libretto for Handel’s Rinaldo, Armide wins back her estranged lover Argante through her “manly” desire for fair combat. Rinaldo is well-respected and loved because he is a valiant warrior, not because he is a lover. In fact, in Rinaldo, he is chided by Goffredo for being momentarily distracted from his duty by his love for Almirena. The above incident also exemplifies how love is represented in both operas. While it brings fleeting joy and ecstasy, it also causes pain and hatred in its wake. It is seen as a selfish endeavor that one could possibly punished for. In Philippe Quinault’s libretto for Armide, the title character turns her back on fighting for her faith and country, instead focusing her powers on forcing Rinaldo to love her. In return for her efforts, she gets her heart broken and loses a portion of her power. Rinaldo himself forsakes Armide’s love to return to war, even though he still has residual feelings for her. In Rinaldo, love also deeply complicates the relationships between Armide, Rinaldo, and their respective lovers, and distracts them from their goals.

On the other hand, the two librettos drastically differ in terms of plot and characters. While the basic storyline in which Armide falls in love with Rinaldo while trying to defeat him stays constant, there are many other discrepancies between the two operas. Handel’s version of the tale includes Almirena and Argante, the lovers of Rinaldo and Armide respectively. As a result, Rinaldo boasts a far more love-centered progression of events, featuring a large amount of interaction between the four lovers. Argante falls in love with Almirena while Armide does the same for Rinaldo. Jealousy and confusion result, and Argante goes to war against Armide for a period of time in the opera. Furthermore, Rinaldo incorporates the appearance of another interesting character: the good sorcerer who helps Goffredo and Eustazio find Armide’s fortress. All these little twists and subplots are completely excluded in Lully’s Armide, in which neither Almirena, Argante or the sorcerer are present. His version is far more simplistic and focuses more on the relationship between the two main characters, as well as the war.

Another major difference between the two operas is their endings. In Lully’s finale, Armide is defeated only in matters of love; she remains unpunished otherwise. She still has her powers, and dissembles her castle in a fit of wrath, flying off to wreak vengeance on Rinaldo. Her grand exit reflects the fact that she is still in control of the situation. However, in Handel’s Rinaldo, the Crusaders enjoy a definite victory over Armide and Argante. The two defeated lovers are so impressed by their enemies’ power that they willingly convert to the Christian faith. The ending of Rinaldo is definitely happier and more politically correct than that of Armide, which is left tantalizingly open.

Besides differences in storyline and characters, the two operas also differ in terms of dramatization and characterization. The two productions were written in distinct time periods and locations, where political climates and operatic traditions were disparate from each other. While Lully and Handel stayed true to certain elements of the story and furnished the main characters with similar personalities, they embellished their respective renditions of the tale with their own inventions and incorporated musical trends of the time into their operas.

One major difference between the two operas is the separation of emotions in characters. Handel’s Rinaldo, being an Opera Seria, pays heed to the Doctrine of Affections, a popular mode of thought at the time, in which rational human beings were believed to experience only one emotion at a time. As a result, his opera shows both Rinaldo and Armide showing at most 2 emotions in their arias. Rinaldo’s aria, “Cara Sposa”, showcases his two conflicting feelings of tenderness and violence, signaling him as a character who is not completely rational. However, these emotions are separated by ritornellos into distinct sections, showing that some semblance of structure still remains. Armide’s conflicting emotions in “Dunque I lacci” and “Ah, crudel” are similarly separated into alternating sections of lamentation and anger. This sense of segregation continues on a broader level throughout the opera; recitatives which denote action and dialogue are sharply distinguished from the more emotive and passionate arias. On the other hand, in Lully’s Tragedie lyrique Armide, both characters show a relative lack of restraint in segmenting their emotions. Set pieces frequently feature a wide range of feelings, all of which are not confined to specific sections. Armide in particular exhibits an impressive amount of emotions in her singing, and Lully allows them to weave together into a colorful tapestry of humors. One example of the fluidity of her emotions is her accompanied recitative “Le Perfide Renaud”, in which she shows the audience her pain, self-pity, regret, wrath, and confusion all in the same song. Also, not only Armide, but other characters in Handel’s Rinaldo are able to make smooth transitions between recitative, aria and other forms of song in between; this serves to further enhance the intergration of different emotions with each other.

Another notable distinction between the two operas is the different vocal roles assigned to Rinaldo. Lully’s self-established form of French opera advocated the use of manly, lower voices in male roles. One possible reason for this was because Rinaldo, being the heroic protagonist of the opera, was designed to represent and exalt the reigning monarch of the time, Louis XIV. As a result, Rinaldo’s part is traditionally sung by a counter-tenor, depicting Rinaldo as masculine and noble. However, Handel chose a higher, soprano voice (traditionally meant to be sung by a castrato) for Rinaldo, as well as other male characters, in his opera. This was because he was conforming to the trend in Italian opera where it was typical for castrati or biological women to take the roles of men. As a result, Handel’s Rinaldo is a much more effeminized, possibly irrational character. This is exemplified by his greater tendency to love and be toyed with by love, as compared to Lully’s Rinaldo. The Rinaldo in Handel’s opera is more prone to being distracted from his duties as a warrior in order to rescue his fiancée.

Lully’s and Handel’s operas both manage to convey the atmosphere of Tasso’s original epic poem effectively. Both operas maintain and reinforce the themes of conquest and love, and how they relate to each other. They also remain reasonably true to the characters and events depicted in the Gerusalemme Liberata. However, this is where most of the similarity ends. Each opera has its own intricacies in detail and design, differing in plot, characterization, and the types of music sung by its characters. It is indeed interesting to observe how each composer adapted this famous story to his own style.

Wednesday, August 12, 2009

Italian Film - The Seduction of Mimi (2007)

Description of film

Double the Seduction, Double the Heartache: an analysis of the parallelism between two incidences of seduction in the film

Mimi and Fiore

Mimi’s seductions of Fiore and Amalia in this film are two very contrasting processes. While there are a few surface similarities that both seductions share, they are far more different in terms of feeling, strategy and motivation, amongst other aspects.

The seductions of both women are similar in that there is a lot of friction between man and woman. Mimi’s Southern upbringing and rough approach to passion clash with Fiore’s emancipated, Northern view of love as something that must be perfect and infused with real feeling. This conflict is exemplified in the couple’s first kiss in the park, where Fiore is shocked by Mimi’s unrefined conduct and refuses to see him again. In Amalia’s case, she offers verbal retaliation in response to Mimi’s initial advances, calling him a “lecher” and telling him to “go away”. Later on, she resists him physically when he tries to perform the actual act of copulation with her; she struggles and screams at him while he restrains her.

Another similarity between the two seductions is that both women are in positions of power. In Fiore’s case, Mimi is so consumed by his love for her that he gives up his backward Sicilian ways and tries to woo her according to her rules. Her hold over his feelings is so great that he actually breaks down when she confesses her love, moved to the point of temporary impotency. Furthermore, their relationship is established on her terms: he is to sleep with no other woman, not even his wife. Such is the extent of her power. As for Amalia, the power she has over Mimi is not emotional, but she is the all-important vessel for his revenge, and he has to follow her orders, making love to her in accordance to her ovulation cycles.

Mimi and Amalia

However, this is where the similarity ends. With regard to the emotional nature of each seduction, there is a great disparity between both. Mimi is deeply in love with Fiore, almost to the point of obsession. His feelings are sincere and heartfelt. In fact, his love is so true that it affects his sexual performance initially, as he is not used to having sex when real feelings are involved. On the other hand, Mimi harbors absolutely no romantic feelings for Amalia; his obsession with seducing her stems only from his need for revenge against Amilcare. His professions of passion (“You drive me crazy”, “Those fiery eyes!”) are flat and insincere, adopting a clichéd seductive tone instead of the earnest, longing tone he uses for Fiore.

There is also a disparity in terms of Mimi’s different approaches to seduction. Mimi exhibits patience in his courtship of Fiore, trying time after time to woo her during walks in the park. He is willing to restrain his passion for the sake of winning her love, at the same time giving her time to consider her feelings. However, when seducing Amalia he dogs her every step, constantly asking her “where and when” they can have a rendezvous. His incessant pursuit lasts only two days as she caves relatively quickly.

Lastly, the motivations behind Mimi’s seductions differ greatly as well. Mimi’s pursuit of Fiore is driven by his sincere love for her, while the force behind his seduction of Amalia is simply revenge and nothing else.

The two seductions serve to contrast one another, as well as subtly show how Mimi changes during the film. Fiore’s seduction takes place near the beginning, where Mimi is taking steps to “become his own man”, emancipating himself from his Southern upbringing. This change is reflected in his new, civilized approach towards courtship. However, Mimi’s seduction of Amalia towards the end of the film brings him back to step one, casting him once again as the traditional Sicilian man bent on rescuing his honor, albeit with a modern twist. His sexual strategy reverts back to one of aggressiveness and violence. The very fact that these two seductions are different from each other is significant in itself; the contrast between them serves to highlight how Mimi learns to be more civilized in Fiore’s case, and how he goes back to primitive Southern standards in Amalia’s case. The concluding message is one of futility and resistance to change.

Double the Seduction, Double the Heartache: an analysis of the parallelism between two incidences of seduction in the film

Mimi and Fiore

Mimi’s seductions of Fiore and Amalia in this film are two very contrasting processes. While there are a few surface similarities that both seductions share, they are far more different in terms of feeling, strategy and motivation, amongst other aspects.

The seductions of both women are similar in that there is a lot of friction between man and woman. Mimi’s Southern upbringing and rough approach to passion clash with Fiore’s emancipated, Northern view of love as something that must be perfect and infused with real feeling. This conflict is exemplified in the couple’s first kiss in the park, where Fiore is shocked by Mimi’s unrefined conduct and refuses to see him again. In Amalia’s case, she offers verbal retaliation in response to Mimi’s initial advances, calling him a “lecher” and telling him to “go away”. Later on, she resists him physically when he tries to perform the actual act of copulation with her; she struggles and screams at him while he restrains her.

Another similarity between the two seductions is that both women are in positions of power. In Fiore’s case, Mimi is so consumed by his love for her that he gives up his backward Sicilian ways and tries to woo her according to her rules. Her hold over his feelings is so great that he actually breaks down when she confesses her love, moved to the point of temporary impotency. Furthermore, their relationship is established on her terms: he is to sleep with no other woman, not even his wife. Such is the extent of her power. As for Amalia, the power she has over Mimi is not emotional, but she is the all-important vessel for his revenge, and he has to follow her orders, making love to her in accordance to her ovulation cycles.

Mimi and Amalia

However, this is where the similarity ends. With regard to the emotional nature of each seduction, there is a great disparity between both. Mimi is deeply in love with Fiore, almost to the point of obsession. His feelings are sincere and heartfelt. In fact, his love is so true that it affects his sexual performance initially, as he is not used to having sex when real feelings are involved. On the other hand, Mimi harbors absolutely no romantic feelings for Amalia; his obsession with seducing her stems only from his need for revenge against Amilcare. His professions of passion (“You drive me crazy”, “Those fiery eyes!”) are flat and insincere, adopting a clichéd seductive tone instead of the earnest, longing tone he uses for Fiore.

There is also a disparity in terms of Mimi’s different approaches to seduction. Mimi exhibits patience in his courtship of Fiore, trying time after time to woo her during walks in the park. He is willing to restrain his passion for the sake of winning her love, at the same time giving her time to consider her feelings. However, when seducing Amalia he dogs her every step, constantly asking her “where and when” they can have a rendezvous. His incessant pursuit lasts only two days as she caves relatively quickly.

Lastly, the motivations behind Mimi’s seductions differ greatly as well. Mimi’s pursuit of Fiore is driven by his sincere love for her, while the force behind his seduction of Amalia is simply revenge and nothing else.

The two seductions serve to contrast one another, as well as subtly show how Mimi changes during the film. Fiore’s seduction takes place near the beginning, where Mimi is taking steps to “become his own man”, emancipating himself from his Southern upbringing. This change is reflected in his new, civilized approach towards courtship. However, Mimi’s seduction of Amalia towards the end of the film brings him back to step one, casting him once again as the traditional Sicilian man bent on rescuing his honor, albeit with a modern twist. His sexual strategy reverts back to one of aggressiveness and violence. The very fact that these two seductions are different from each other is significant in itself; the contrast between them serves to highlight how Mimi learns to be more civilized in Fiore’s case, and how he goes back to primitive Southern standards in Amalia’s case. The concluding message is one of futility and resistance to change.

Globalization and Women's Political Power (2006)

The process of globalization can be separated into a few different aspects; mainly social, economic, and political. Not only does globalization cover a broad range of fields, but it also influences and is influenced by countless individuals on a day-to-day basis. The focus of this essay will be on how women in particular are able to act as agents to one specific aspect of globalization: politics. In this context, an agent could be referred to as a person who acts or has the power or authority to act. On the other hand, politics would be defined here as “social relations involving authority or power”. While politics could be associated with government and state relations, it may not always be the case as women still lack institutional power in certain countries. Thus, we will also take a look at politics on the level of local communities and societies.

Women acting as agents are generally found to do so through the impacts of their actions on their societies and cultures, to achieve a certain goal – which, in this case, is a change in the structure of political power throughout the world. They may not necessarily be conscious of the significance of their actions, nor may they be aware of their political outcomes. However, this does not change the fact that women are impacting the political structures of their societies and cultures, slowly but surely. One observable trend of globalization in politics is the rise in soft power versus hard power over the years. According to Joseph S. Nye, the success of soft power, or co-optive power, rests in “the attractiveness of one’s culture and values or the ability to manipulate the agenda of political choices”, in lieu of hard power’s strategy of coercion and intimidation. Western principles like democracy and equal opportunities for women and men are being disseminated throughout the globe to other nations through global media like the Internet and television, and the actions of women both support and contribute to this phenomenon. However, that does not mean that women embrace other forms of globalization; many find themselves marginalized by global phenomena such as modernization and unequal economic development. This essay will examine how women support and repel different forces of globalization, simultaneously taking a closer look at power shifts within oppressive societies.

Feminism and democracy in the Middle-East

Muslim countries in Middle-East are notorious for the subjugation and mistreatment of women, oft under the pretext of following the rules of Islam. Under a well-established patriarchal system, women are seen as one step below men in the social hierarchy. They are denied the authority, as well as social and economic privileges that most men of similar age have. Tradition dictates that only when they have the support of their families are women, not being property owners themselves, able to gain some form of power and status; this results in their being bound to follow patriarchal norms, in and out of the house.

However, Suad J. Joseph and Susan Slyomovics state in their introduction to “Women and Power in the Middle East” that feminist activists in a number of countries have lobbied to change family laws such that family, religion and the individual are intertwined to a lesser degree. While there has been little significant progress in that department, the victories won by feminists in countries like Iraq, Morocco, and Yemen are still far from negligible. Furthermore, another significant political movement is being helped along by the actions of women: the spread of democracy. Nayereh Tohidi states that “pushed by the forces of globalization, young Iranians in Iran and elsewhere – young Iranian American women in particular – are nudging [Iran] toward genuine progress [in democratic reform]”. Younger Iranians, being more educated and more literate than their predecessors, are pushing for “more liberal sexual mores and secularization of politics”. Furthermore, Iran’s past history of negotiation with modernity – the Constitutional Revolution (1906-11) and the Islamic Revolution (1978-79) – has taught Iranian women to contend with the patriarchal system by using their political muscle and prepared the nation for democracy. The movement has been so strong that even pro-government Islamic women have been influenced by Muslim feminism and have learnt to query Islam’s social system. Is Islam truly about putting men in the positions of power and subjugating women to their whims? Should the government be a mere extension of Islam or should it be separated from religion? These are some of the questions that Muslim women are beginning to ask, as they become more exposed to Western ideologies through U.N.-sponsored conferences, contact with global feminist networks, the Internet and Iranians who have left the country.

Women’s narratives of the supernatural in the Ecuadorian Andes: a demonstration of resistance

The 1960s-70s saw the implementation of farming methods of the Green Revolution in countries around the world. These were capital-intensive methods that involved the buying of new strains of seeds and machinery, thus giving large agribusinesses and commercial farmers with economies of scale the monetary advantage over peasants using traditional agricultural methods. Traditional farmers found themselves marginalized by the shift from labor-intensive to capital-intensive production; for instance, peasants in the Ecuadorian Andes found themselves selling off most of their land to commercial farmers. Being left with insufficient or no land to support themselves, they sought jobs in the very agribusinesses that had initially deprived them of their livelihoods. Peasants in the employ of commercial farmers found themselves subject to low pay, long hours and dangerous working conditions. Furthermore, women in particular were even more marginalized; agribusinesses favored the employment of male laborers, and many women found themselves excluded from the new trend of commercial farming.

According to Mary M. Crain, female peasants, not being employed by agribusiness and thus having more freedom to criticize commercial farmers than their male counterparts, started to associate technology, machinery, and anything that represented commercial farming with the devil, circulating stories of devil possession and death. The devil appeared in various guises, more often than not in a physical form similar to Caucasian Americans, sometimes accompanied by the temptation of ill-gotten material wealth. These narratives all had a similar structure: a male employee working in one of the capitalist farms would become possessed by an evil spirit, often falling sick or dying. Crain believed that the narratives were “prominent idiom[s] for talking about material change and the women’s opposition to that change”. She also referred to the narratives as “coded political language” for peasant women to communicate in. Women were able to make use of gossip to “shape public opinion and alter power relations in a community”, subtly acting out against not only oppression under capitalist outsiders, but even the male peasants in the community as well.

As commercial farmers work with other institutions to quench political expression, women limit their discussion of devil possessions only to themselves and their communities, making it difficult for the dominant organizations, being outsiders, to monitor their dialogue. By refusing to collaborate with outsiders and impart information to them, these women are putting on a form of positive resistance against the infiltration of their societies by outsiders. While capitalists may have wrestled economic power away from the peasants, they still maintain some form of underground political power through verbal communication.

On a different level, women also pose a challenge to the male hierarchy through their gossip. Unlike feminists in the Middle-East, female peasants in the Andes demonstrate their subversion in more subtle ways. Using gossip, women compensate for their lack of institutional power by using their verbal skills to mould people’s opinions. While women’s speech has often been devalued in public settings, they can still exert power from their “domestic domains”; Crain cites the forced resignation of Caesar Pilas, a vice-president of the community and thus an individual of high standing, as a result of women’s gossip. Furthermore, the employment of men in commercial farms has been a blessing in disguise for women in these peasant communities; the absence of men has left space for more women to participate in public assemblies and occupy positions of power in the local government.

Again, this shows the increasing importance of soft power over hard power in today’s world. Capitalist outsiders may have the upper hand economically, but women have a subtler form of influence in their verbal communication and spreading of ideas within the community.

Women’s roles in increasing awareness of AIDS in Africa

AIDS is the global plague of modern times. Its influence ranges far and wide, and it is still spreading at alarming rates. Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the foremost breeding grounds for this virus, accounting for nearly 65% of the people living with HIV or AIDS in 2005. Women are as much victims of AIDS as are men and children.

The propagation of AIDS in Africa could possibly have been catalyzed by one effect of globalization: mobilization of labor. According to Edwin Bayrd, AIDS was most likely spread to smaller villages by young men and women who left the community in the seeking work in large cities. This contributed to the sex trade, as lonely men and women searched for companionship and comfort away from home. Promiscuity spurred on the spread of AIDS at a rapid pace, and as these men and women grew sick and unable to work, they returned home to their villages.

People in these smaller villages remained silent and shameful about their plights, unaware of the actual cause. Not only insufficient awareness, but a lack of funds for proper healthcare and stigmatizing of AIDS patients have contributed to the virus’ death toll. However, there is evidence that this problem could be alleviated through increased awareness of AIDS, and local women have been able to play a major role in this solution. Take for example the village of Hamburg, where many women and a handful of men gathered together to create a masterpiece inspired by their sense of community in the face of AIDS. This project, the Keiskamma Altarpiece, was organized by Dr. Carol Hofmeyr, the village’s AIDS doctor, with the goal of bringing the people of Hamburg together to commemorate the lives lost to AIDS and console those left behind. The altarpiece reflects how Hamburg was ravaged by AIDS in the beginning, and how the villagers are now learning to cope with it, slowly but surely; it is a symbol of their ability to “rise above adversity”.

From a broader perspective, the altarpiece also serves as a wonderful example of the women’s ability to reach out to people and make them think. By exhibiting this altarpiece in North America, viewers of this spectacular work of art have been allowed a glimpse into Hamburg as its residents see it; a beautiful place that has unfortunately suffered the ravages of the AIDS pandemic. Even though the women of Hamburg are for the most part unable to physically communicate with people in other nations, they are indirectly doing so through their art, sending the important message of how AIDS is affecting their lives to all who view the altarpiece. By increasing awareness of AIDS in Africa through their artwork, the women of Hamburg are actually exercising some form of political power, in that they are able to transcend the oppressiveness and inefficiency of the African government and healthcare system to move people in other countries; people who could potentially contribute to helping AIDS-stricken Africa to recover.

Conclusion

Women around the world do have some form of political clout, even in countries with oppressive, patriarchal social systems. It is with this political power that they are able to act as cultural and social agents to the political aspect of globalization, such as promoting equality between men and women and supporting the rise of democracy in different parts of the world. It is rather ironic, however, that at times they can use this power to oppose other forces of globalization – for example, modernization and capitalism in the Ecuadorian Andes. However, I believe that the rising trend in feminine power over the years is a positive thing, as it has had observable effects on power relations in oppressed societies. Hopefully this phenomenon will continue and grow stronger over the years; it may not be too much to hope for a future where men and women are given equal treatment all over the world.

Bibliography

Nye, Joseph S. 2004. Soft Power,1st ed. p. 7. United States: Public Affairs.

Suad, Joseph, and Susan Slyomovics. 2001. “Introduction”, in Women and Power in the Middle-East, pp. 1-14. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Crain, Mary M. 1991. “Poetics and Politics in the Ecuadorean Andes”, American Ethnologist, vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 67-82.

"agent." The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. 09 Dec. 2006.

"politics." WordNet® 2.1. Princeton University. 10 Dec. 2006.

Tohidi, Nayereh. “Revolution? What's in it for them?” Available at: http://www.latimes.com/news/opinion/sunday/commentary/la-op-iranwomen31jul31,0,7192154.story?coll=la-home-sunday-opinion. 11 Dec 2006.

“AMREF – What we do – PIA.” Available at: http://www.amref.org/index.asp?PageID=50&PiaID=2. 11 Dec 2006.

Women acting as agents are generally found to do so through the impacts of their actions on their societies and cultures, to achieve a certain goal – which, in this case, is a change in the structure of political power throughout the world. They may not necessarily be conscious of the significance of their actions, nor may they be aware of their political outcomes. However, this does not change the fact that women are impacting the political structures of their societies and cultures, slowly but surely. One observable trend of globalization in politics is the rise in soft power versus hard power over the years. According to Joseph S. Nye, the success of soft power, or co-optive power, rests in “the attractiveness of one’s culture and values or the ability to manipulate the agenda of political choices”, in lieu of hard power’s strategy of coercion and intimidation. Western principles like democracy and equal opportunities for women and men are being disseminated throughout the globe to other nations through global media like the Internet and television, and the actions of women both support and contribute to this phenomenon. However, that does not mean that women embrace other forms of globalization; many find themselves marginalized by global phenomena such as modernization and unequal economic development. This essay will examine how women support and repel different forces of globalization, simultaneously taking a closer look at power shifts within oppressive societies.

Feminism and democracy in the Middle-East

Muslim countries in Middle-East are notorious for the subjugation and mistreatment of women, oft under the pretext of following the rules of Islam. Under a well-established patriarchal system, women are seen as one step below men in the social hierarchy. They are denied the authority, as well as social and economic privileges that most men of similar age have. Tradition dictates that only when they have the support of their families are women, not being property owners themselves, able to gain some form of power and status; this results in their being bound to follow patriarchal norms, in and out of the house.

However, Suad J. Joseph and Susan Slyomovics state in their introduction to “Women and Power in the Middle East” that feminist activists in a number of countries have lobbied to change family laws such that family, religion and the individual are intertwined to a lesser degree. While there has been little significant progress in that department, the victories won by feminists in countries like Iraq, Morocco, and Yemen are still far from negligible. Furthermore, another significant political movement is being helped along by the actions of women: the spread of democracy. Nayereh Tohidi states that “pushed by the forces of globalization, young Iranians in Iran and elsewhere – young Iranian American women in particular – are nudging [Iran] toward genuine progress [in democratic reform]”. Younger Iranians, being more educated and more literate than their predecessors, are pushing for “more liberal sexual mores and secularization of politics”. Furthermore, Iran’s past history of negotiation with modernity – the Constitutional Revolution (1906-11) and the Islamic Revolution (1978-79) – has taught Iranian women to contend with the patriarchal system by using their political muscle and prepared the nation for democracy. The movement has been so strong that even pro-government Islamic women have been influenced by Muslim feminism and have learnt to query Islam’s social system. Is Islam truly about putting men in the positions of power and subjugating women to their whims? Should the government be a mere extension of Islam or should it be separated from religion? These are some of the questions that Muslim women are beginning to ask, as they become more exposed to Western ideologies through U.N.-sponsored conferences, contact with global feminist networks, the Internet and Iranians who have left the country.

Women’s narratives of the supernatural in the Ecuadorian Andes: a demonstration of resistance

The 1960s-70s saw the implementation of farming methods of the Green Revolution in countries around the world. These were capital-intensive methods that involved the buying of new strains of seeds and machinery, thus giving large agribusinesses and commercial farmers with economies of scale the monetary advantage over peasants using traditional agricultural methods. Traditional farmers found themselves marginalized by the shift from labor-intensive to capital-intensive production; for instance, peasants in the Ecuadorian Andes found themselves selling off most of their land to commercial farmers. Being left with insufficient or no land to support themselves, they sought jobs in the very agribusinesses that had initially deprived them of their livelihoods. Peasants in the employ of commercial farmers found themselves subject to low pay, long hours and dangerous working conditions. Furthermore, women in particular were even more marginalized; agribusinesses favored the employment of male laborers, and many women found themselves excluded from the new trend of commercial farming.

According to Mary M. Crain, female peasants, not being employed by agribusiness and thus having more freedom to criticize commercial farmers than their male counterparts, started to associate technology, machinery, and anything that represented commercial farming with the devil, circulating stories of devil possession and death. The devil appeared in various guises, more often than not in a physical form similar to Caucasian Americans, sometimes accompanied by the temptation of ill-gotten material wealth. These narratives all had a similar structure: a male employee working in one of the capitalist farms would become possessed by an evil spirit, often falling sick or dying. Crain believed that the narratives were “prominent idiom[s] for talking about material change and the women’s opposition to that change”. She also referred to the narratives as “coded political language” for peasant women to communicate in. Women were able to make use of gossip to “shape public opinion and alter power relations in a community”, subtly acting out against not only oppression under capitalist outsiders, but even the male peasants in the community as well.

As commercial farmers work with other institutions to quench political expression, women limit their discussion of devil possessions only to themselves and their communities, making it difficult for the dominant organizations, being outsiders, to monitor their dialogue. By refusing to collaborate with outsiders and impart information to them, these women are putting on a form of positive resistance against the infiltration of their societies by outsiders. While capitalists may have wrestled economic power away from the peasants, they still maintain some form of underground political power through verbal communication.

On a different level, women also pose a challenge to the male hierarchy through their gossip. Unlike feminists in the Middle-East, female peasants in the Andes demonstrate their subversion in more subtle ways. Using gossip, women compensate for their lack of institutional power by using their verbal skills to mould people’s opinions. While women’s speech has often been devalued in public settings, they can still exert power from their “domestic domains”; Crain cites the forced resignation of Caesar Pilas, a vice-president of the community and thus an individual of high standing, as a result of women’s gossip. Furthermore, the employment of men in commercial farms has been a blessing in disguise for women in these peasant communities; the absence of men has left space for more women to participate in public assemblies and occupy positions of power in the local government.

Again, this shows the increasing importance of soft power over hard power in today’s world. Capitalist outsiders may have the upper hand economically, but women have a subtler form of influence in their verbal communication and spreading of ideas within the community.

Women’s roles in increasing awareness of AIDS in Africa

AIDS is the global plague of modern times. Its influence ranges far and wide, and it is still spreading at alarming rates. Sub-Saharan Africa is one of the foremost breeding grounds for this virus, accounting for nearly 65% of the people living with HIV or AIDS in 2005. Women are as much victims of AIDS as are men and children.

The propagation of AIDS in Africa could possibly have been catalyzed by one effect of globalization: mobilization of labor. According to Edwin Bayrd, AIDS was most likely spread to smaller villages by young men and women who left the community in the seeking work in large cities. This contributed to the sex trade, as lonely men and women searched for companionship and comfort away from home. Promiscuity spurred on the spread of AIDS at a rapid pace, and as these men and women grew sick and unable to work, they returned home to their villages.

People in these smaller villages remained silent and shameful about their plights, unaware of the actual cause. Not only insufficient awareness, but a lack of funds for proper healthcare and stigmatizing of AIDS patients have contributed to the virus’ death toll. However, there is evidence that this problem could be alleviated through increased awareness of AIDS, and local women have been able to play a major role in this solution. Take for example the village of Hamburg, where many women and a handful of men gathered together to create a masterpiece inspired by their sense of community in the face of AIDS. This project, the Keiskamma Altarpiece, was organized by Dr. Carol Hofmeyr, the village’s AIDS doctor, with the goal of bringing the people of Hamburg together to commemorate the lives lost to AIDS and console those left behind. The altarpiece reflects how Hamburg was ravaged by AIDS in the beginning, and how the villagers are now learning to cope with it, slowly but surely; it is a symbol of their ability to “rise above adversity”.

From a broader perspective, the altarpiece also serves as a wonderful example of the women’s ability to reach out to people and make them think. By exhibiting this altarpiece in North America, viewers of this spectacular work of art have been allowed a glimpse into Hamburg as its residents see it; a beautiful place that has unfortunately suffered the ravages of the AIDS pandemic. Even though the women of Hamburg are for the most part unable to physically communicate with people in other nations, they are indirectly doing so through their art, sending the important message of how AIDS is affecting their lives to all who view the altarpiece. By increasing awareness of AIDS in Africa through their artwork, the women of Hamburg are actually exercising some form of political power, in that they are able to transcend the oppressiveness and inefficiency of the African government and healthcare system to move people in other countries; people who could potentially contribute to helping AIDS-stricken Africa to recover.

Conclusion

Women around the world do have some form of political clout, even in countries with oppressive, patriarchal social systems. It is with this political power that they are able to act as cultural and social agents to the political aspect of globalization, such as promoting equality between men and women and supporting the rise of democracy in different parts of the world. It is rather ironic, however, that at times they can use this power to oppose other forces of globalization – for example, modernization and capitalism in the Ecuadorian Andes. However, I believe that the rising trend in feminine power over the years is a positive thing, as it has had observable effects on power relations in oppressed societies. Hopefully this phenomenon will continue and grow stronger over the years; it may not be too much to hope for a future where men and women are given equal treatment all over the world.

Bibliography

Nye, Joseph S. 2004. Soft Power,1st ed. p. 7. United States: Public Affairs.

Suad, Joseph, and Susan Slyomovics. 2001. “Introduction”, in Women and Power in the Middle-East, pp. 1-14. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Crain, Mary M. 1991. “Poetics and Politics in the Ecuadorean Andes”, American Ethnologist, vol. 18, No. 1, pp. 67-82.

"agent." The American Heritage® Dictionary of the English Language, Fourth Edition. Houghton Mifflin Company, 2004. 09 Dec. 2006.

"politics." WordNet® 2.1. Princeton University. 10 Dec. 2006.

Tohidi, Nayereh. “Revolution? What's in it for them?” Available at: http://www.latimes.com/news/opinion/sunday/commentary/la-op-iranwomen31jul31,0,7192154.story?coll=la-home-sunday-opinion. 11 Dec 2006.

“AMREF – What we do – PIA.” Available at: http://www.amref.org/index.asp?PageID=50&PiaID=2. 11 Dec 2006.

Cats (2003)

They came, as a group. Slowly, silently, slinking along in the dark shadows of the dusk. Letting out barely audible “meows” of apprehension, they continued in a writhing Indian file down the length of the garden wall, until they finally reached their destination for the night.

One by one, three bodies, covered in fur, slid down from their temporary perch at the corner of the hedge. Motions fluid, eyes bright and alert, the graceful felines dropped paws-first onto the ground, now earthbound. Upon landing, they darted almost immediately into the foreboding depths below the hedge, like experienced war veterans of times long past.

Once their safety from prying eyes, human or otherwise, was assured, each of them settled down, grooming themselves, licking their paws, or digging in earnest at the damp dirt to unearth possible tidbits that had been overlooked by the other inhabitants of the area. However, this was not enough to bide the time till dawn, and they paced restlessly, wearing shallow little furrows into the soil beneath their feet. Silence stretched over them, thick and serene, in contrast to their agitated little movements of disquiet.

Soon, their waiting was rewarded. Over the soundlessness of the night, they heard a series of scuffling and squeaks. Though soft, they were like rolls of thunder to the experienced ears of predators. Pointed ears perked up collectively, the felines bounded to the source of the noise, an unlucky rodent with its pink snout stuck in a rusting drainpipe.

The rat was a masterpiece of its kind. Its ears were large in diameter, fur unusually fine and silver for the species, whiskers long and white, gleaming in the moonlight. But cats do not care much for the appearance of their prey, and this case was no exception. The tabby, striped like a tiger and possessing the ferocity of one, was the first to make a move. It pounced, hind legs uncoiling like a wound-up spring, and struck a lethal blow to the rat’s neck. The game was dead, and the hunt over. The members of the pack came together, greedily snapping juicy red meat off the bones of their prey.

Once more they trooped back to the hedge, curling up into tight balls of fur upon reaching their nest. The feast had been good, the portions satisfactory, and their stomachs were filled to the brim. Snuggling closer for warmth, the three of them gradually succumbed to the fatigue brought on by the excitement of their kill, purring contentedly in the aftermath of the meal.

By the time the first awoke, dawn had broken and the sun had just begun its journey to the edge of the sky, peeking timidly over the rooftops and bathing the entire neighbourhood in its all-encompassing yellow glow. Not even the dense bush above the threesome could stop some fraction of the rays from reaching through to below. Shaking its body free of dust and dirt, the early riser stood and stretched, savouring the feeling of warmth on its spotted pelt. The sudden movement jolted the other two awake, and they too rose up for a mild morning exercise to shake away stiff joints and soothe aching muscles.

The start of a new day brought on many new sensations. Once awake and refreshed, the cats began to feel the first gnawing of renewed hunger in their stomachs. Hopping lightly to their feet, they scouted the garden for miscellaneous scraps of food, scouring the entire area with the practiced ease of born scavengers. However, their search proved fruitless, and though they investigated every inch of the ground they could find no sustenance. Eventually they assembled below the family van that lay parked so imperiously in the driveway, wearing apparent looks of disgust on their delicate features.

“Forget it, nothing edible here,” their expressions seemed to say. Defeated and bored, they paced around under their new hiding place, pawing and sniffing at the ground with idle curiosity.

Eventually the sun climbed higher into the sky, and the sound of a door creaking open could be heard over the cacophony of chirping caused by the birds. Footsteps, sharp and accented, wove a trail towards the cats, followed by a click of a car door. They turned as one, just in time to see a stiletto clad foot soaring overhead, stepping into the car’s interior. Soon enough the engine sputtered to life in a terrifying roar, shaking the entire surface of the vehicle above their heads. Utterly aghast at the sudden turn of events, the three felines fled in panic, scattering in a haphazard line towards the front of the van and over the red brick walls of their enclosure.

The driver, sitting within the confines of her vehicle, was startled for a second, then leaned back into the seat and shrugged to herself.

“Cats.”

One by one, three bodies, covered in fur, slid down from their temporary perch at the corner of the hedge. Motions fluid, eyes bright and alert, the graceful felines dropped paws-first onto the ground, now earthbound. Upon landing, they darted almost immediately into the foreboding depths below the hedge, like experienced war veterans of times long past.

Once their safety from prying eyes, human or otherwise, was assured, each of them settled down, grooming themselves, licking their paws, or digging in earnest at the damp dirt to unearth possible tidbits that had been overlooked by the other inhabitants of the area. However, this was not enough to bide the time till dawn, and they paced restlessly, wearing shallow little furrows into the soil beneath their feet. Silence stretched over them, thick and serene, in contrast to their agitated little movements of disquiet.

Soon, their waiting was rewarded. Over the soundlessness of the night, they heard a series of scuffling and squeaks. Though soft, they were like rolls of thunder to the experienced ears of predators. Pointed ears perked up collectively, the felines bounded to the source of the noise, an unlucky rodent with its pink snout stuck in a rusting drainpipe.

The rat was a masterpiece of its kind. Its ears were large in diameter, fur unusually fine and silver for the species, whiskers long and white, gleaming in the moonlight. But cats do not care much for the appearance of their prey, and this case was no exception. The tabby, striped like a tiger and possessing the ferocity of one, was the first to make a move. It pounced, hind legs uncoiling like a wound-up spring, and struck a lethal blow to the rat’s neck. The game was dead, and the hunt over. The members of the pack came together, greedily snapping juicy red meat off the bones of their prey.

Once more they trooped back to the hedge, curling up into tight balls of fur upon reaching their nest. The feast had been good, the portions satisfactory, and their stomachs were filled to the brim. Snuggling closer for warmth, the three of them gradually succumbed to the fatigue brought on by the excitement of their kill, purring contentedly in the aftermath of the meal.

By the time the first awoke, dawn had broken and the sun had just begun its journey to the edge of the sky, peeking timidly over the rooftops and bathing the entire neighbourhood in its all-encompassing yellow glow. Not even the dense bush above the threesome could stop some fraction of the rays from reaching through to below. Shaking its body free of dust and dirt, the early riser stood and stretched, savouring the feeling of warmth on its spotted pelt. The sudden movement jolted the other two awake, and they too rose up for a mild morning exercise to shake away stiff joints and soothe aching muscles.

The start of a new day brought on many new sensations. Once awake and refreshed, the cats began to feel the first gnawing of renewed hunger in their stomachs. Hopping lightly to their feet, they scouted the garden for miscellaneous scraps of food, scouring the entire area with the practiced ease of born scavengers. However, their search proved fruitless, and though they investigated every inch of the ground they could find no sustenance. Eventually they assembled below the family van that lay parked so imperiously in the driveway, wearing apparent looks of disgust on their delicate features.

“Forget it, nothing edible here,” their expressions seemed to say. Defeated and bored, they paced around under their new hiding place, pawing and sniffing at the ground with idle curiosity.

Eventually the sun climbed higher into the sky, and the sound of a door creaking open could be heard over the cacophony of chirping caused by the birds. Footsteps, sharp and accented, wove a trail towards the cats, followed by a click of a car door. They turned as one, just in time to see a stiletto clad foot soaring overhead, stepping into the car’s interior. Soon enough the engine sputtered to life in a terrifying roar, shaking the entire surface of the vehicle above their heads. Utterly aghast at the sudden turn of events, the three felines fled in panic, scattering in a haphazard line towards the front of the van and over the red brick walls of their enclosure.

The driver, sitting within the confines of her vehicle, was startled for a second, then leaned back into the seat and shrugged to herself.

“Cats.”

The Age of Imagination: Japanese Art, 1615-1868, from the Price Collection – Encore (2009)

Details about the exhibition

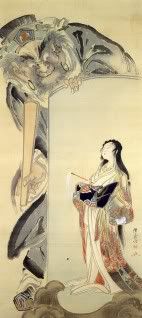

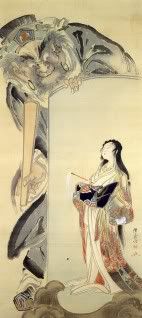

Kawanabe Kyosai, The King of Hell with a Courtesan

The Age of Imagination: Japanese Art, 1615 - 1868 is a visionary exhibition that allows the viewer a valuable glimpse into the art of Japan’s Edo period. The collection of paintings on display consists of a myriad of diverse styles, philosophies and subject matter – fitting indeed for the theme of creative progression that is characteristic of the Edo period. The exhibition encompasses many aspects of traditional Japanese art: religious depictions, genre paintings, and landscapes all make their appearances through an array of forms and mediums. The viewer is able to emerge from his experience satisfied in the knowledge that he has seen a comprehensive and fair representation of Edo-era painting.

In order to capture the holistic nature of The Age of Imagination, I have selected several pieces ranging across an eclectic mix of artists and styles to write about. A work that caught my eye early on in the exhibition is The Death of the Buddha by Nakamichi Sadasue (c. 18th century), a hanging scroll painted with ink and colors on paper. The scroll depicts a Buddha – presumably Shaka – in the process of entering nirvana, surrounded by disciples, other deities and animals. His mother, Queen Maya, also makes an appearance in the top right corner, descending from the heavens with an entourage behind her. It was interesting to note that this painting has much in common with Nirvana of the Buddha (c. 711) at the Horyuji Pagoda, which is a depiction scene of the death of Shaka using the medium of clay sculptures. Both works share very similar layouts, with the Buddha figure reclining on a pedestal in the center of the tableau, surrounded by his consorts, and Maya at the corner. Furthermore, like its predecessor from the Nara period, Sadasue’s work shows some obvious iconographical traits. Firstly, there is a clear distinction between the appearances of the disciples (Hinayana) and the bodhisattvas (Mahayana): the disciples form a weeping, bedraggled lot, evidence of their incomplete mastery of the Buddha’s instruction, while the bodhisattvas look on impassively, understanding that death is but a means to an end for the Buddha. Secondly, a golden skin tone marks the Buddha and bodhisattvas as divine beings. (However, in the case of the Horyuji sculptures, only Shaka is imbued with the golden skin). Of course, there are certain aspects to Sadasue’s painting that set it apart from the Horyuji tableau and give it a slightly more modern quality. Decorative elements are emphasized over realism – clouds, trees and water are painted with an abstract flair – and the artist plays with size and perspective – the Buddha is very large in comparison to everyone else, perhaps to emphasize his presence, while Maya seems shrunken down to show that she is further away.

Another work of interest is Soga Shohaku’s Wild Horses (c. 18th century), a pair of six folding screens, done with ink and gold on paper. This painting has a surprisingly impressionistic quality to it. Several horses are painted in different positions and poses across the screens, the dynamism of their movements exaggerated through varied, almost haphazard brushwork. Traditional attention to detail and refined line work are substituted in favor of bold, thick strokes. Also worth noting is Shohaku’s use of empty space in the work. The lack of any background elements in the painting serves to focus the viewer’s attention solely on the horses; indeed, the energy emanating from the subjects is more than sufficient to draw the viewer in and hold his interest. The dynamism inherent in the painting, as well as the artist’s effective use of blank space to further enhance it, seems reminiscent of another Edo period painting in the decorative tradition: Wind and Thunder Gods by Sotatsu.

However, Wild Horses offers but a small glimpse of Shohaku’s artistic versatility. In another of his paintings showcased in the same exhibition, Mount Fuji and Seiken-ji Temple at Miho (c. 18th century), Shohaku uses a completely different style, appropriate to the subject matter. Unlike the relatively abstract, almost careless brush techniques used in Wild Horses to bring out the uncontained energy of the horses, Shohaku uses a more archaic painting style to depict the Mount Fuji and its surroundings in all its age and grandeur. This does not in fact signal an evolution in painting style, but an ability to adapt different styles to fit different themes. Mount Fuji and Seiken-ji Temple at Miho leans more toward realism and boasts a refined painting style, with straightforward use of perspective and high visual accuracy. The only thing one can find in common with Wild Horses is Shohaku’s use of blank, flat space, this time used to give the impression of distance. The foreground of the painting is more detailed and strongly rendered with shading, while the background gets gradually lighter and more washed out, till Mount Fuji is simply a white shape against the sky.

The King of Hell with a Courtesan (c. 19th century) by Kawanabe Kyosai – a hanging scroll with ink and colors on silk – is a refreshingly humorous piece, fitting with the caricatural tone of many of his other works. In it, Enma the king of hell, dressed as a Chinese judge, is gazing with ill-contained delight at the courtesan of hell, Jigoku Dayu, in a mirror. What drew my interest were the contrasting styles of painting used within the work itself. The king, being a large, burly figure lacking in subtlety, is painted quite roughly, using thick coarse brushstrokes. The courtesan, who has much smaller proportions, is finely painted; her hair, facial features and kimono convey a sense of delicacy. One could go further to observe that painting style used for Enma is given a more modern treatment than the understated lines of the courtesan, which could be seen as faithful to a more archaic style. The extremity of styles juxtaposed next to each other also contributes to the cartoonish feel of the piece, which is exacerbated by the exaggerated smile and slightly “wild” eyes of Enma. Kyosai, like Shohaku, is able to harness different styles of painting to suit his work, except he goes a step further in this case to combine two styles in one piece.

With such an eclectic range of styles and genres developing in the same era, it is no wonder the Edo period has been hailed as “the age of imagination” in Japanese art. In building on the rich artistic and cultural traditions of past historical periods, yet embracing more modern approaches, artists of the Edo made no small contribution to the evolution of Japanese art over the years.

Kawanabe Kyosai, The King of Hell with a Courtesan

The Age of Imagination: Japanese Art, 1615 - 1868 is a visionary exhibition that allows the viewer a valuable glimpse into the art of Japan’s Edo period. The collection of paintings on display consists of a myriad of diverse styles, philosophies and subject matter – fitting indeed for the theme of creative progression that is characteristic of the Edo period. The exhibition encompasses many aspects of traditional Japanese art: religious depictions, genre paintings, and landscapes all make their appearances through an array of forms and mediums. The viewer is able to emerge from his experience satisfied in the knowledge that he has seen a comprehensive and fair representation of Edo-era painting.

In order to capture the holistic nature of The Age of Imagination, I have selected several pieces ranging across an eclectic mix of artists and styles to write about. A work that caught my eye early on in the exhibition is The Death of the Buddha by Nakamichi Sadasue (c. 18th century), a hanging scroll painted with ink and colors on paper. The scroll depicts a Buddha – presumably Shaka – in the process of entering nirvana, surrounded by disciples, other deities and animals. His mother, Queen Maya, also makes an appearance in the top right corner, descending from the heavens with an entourage behind her. It was interesting to note that this painting has much in common with Nirvana of the Buddha (c. 711) at the Horyuji Pagoda, which is a depiction scene of the death of Shaka using the medium of clay sculptures. Both works share very similar layouts, with the Buddha figure reclining on a pedestal in the center of the tableau, surrounded by his consorts, and Maya at the corner. Furthermore, like its predecessor from the Nara period, Sadasue’s work shows some obvious iconographical traits. Firstly, there is a clear distinction between the appearances of the disciples (Hinayana) and the bodhisattvas (Mahayana): the disciples form a weeping, bedraggled lot, evidence of their incomplete mastery of the Buddha’s instruction, while the bodhisattvas look on impassively, understanding that death is but a means to an end for the Buddha. Secondly, a golden skin tone marks the Buddha and bodhisattvas as divine beings. (However, in the case of the Horyuji sculptures, only Shaka is imbued with the golden skin). Of course, there are certain aspects to Sadasue’s painting that set it apart from the Horyuji tableau and give it a slightly more modern quality. Decorative elements are emphasized over realism – clouds, trees and water are painted with an abstract flair – and the artist plays with size and perspective – the Buddha is very large in comparison to everyone else, perhaps to emphasize his presence, while Maya seems shrunken down to show that she is further away.

Another work of interest is Soga Shohaku’s Wild Horses (c. 18th century), a pair of six folding screens, done with ink and gold on paper. This painting has a surprisingly impressionistic quality to it. Several horses are painted in different positions and poses across the screens, the dynamism of their movements exaggerated through varied, almost haphazard brushwork. Traditional attention to detail and refined line work are substituted in favor of bold, thick strokes. Also worth noting is Shohaku’s use of empty space in the work. The lack of any background elements in the painting serves to focus the viewer’s attention solely on the horses; indeed, the energy emanating from the subjects is more than sufficient to draw the viewer in and hold his interest. The dynamism inherent in the painting, as well as the artist’s effective use of blank space to further enhance it, seems reminiscent of another Edo period painting in the decorative tradition: Wind and Thunder Gods by Sotatsu.

However, Wild Horses offers but a small glimpse of Shohaku’s artistic versatility. In another of his paintings showcased in the same exhibition, Mount Fuji and Seiken-ji Temple at Miho (c. 18th century), Shohaku uses a completely different style, appropriate to the subject matter. Unlike the relatively abstract, almost careless brush techniques used in Wild Horses to bring out the uncontained energy of the horses, Shohaku uses a more archaic painting style to depict the Mount Fuji and its surroundings in all its age and grandeur. This does not in fact signal an evolution in painting style, but an ability to adapt different styles to fit different themes. Mount Fuji and Seiken-ji Temple at Miho leans more toward realism and boasts a refined painting style, with straightforward use of perspective and high visual accuracy. The only thing one can find in common with Wild Horses is Shohaku’s use of blank, flat space, this time used to give the impression of distance. The foreground of the painting is more detailed and strongly rendered with shading, while the background gets gradually lighter and more washed out, till Mount Fuji is simply a white shape against the sky.

The King of Hell with a Courtesan (c. 19th century) by Kawanabe Kyosai – a hanging scroll with ink and colors on silk – is a refreshingly humorous piece, fitting with the caricatural tone of many of his other works. In it, Enma the king of hell, dressed as a Chinese judge, is gazing with ill-contained delight at the courtesan of hell, Jigoku Dayu, in a mirror. What drew my interest were the contrasting styles of painting used within the work itself. The king, being a large, burly figure lacking in subtlety, is painted quite roughly, using thick coarse brushstrokes. The courtesan, who has much smaller proportions, is finely painted; her hair, facial features and kimono convey a sense of delicacy. One could go further to observe that painting style used for Enma is given a more modern treatment than the understated lines of the courtesan, which could be seen as faithful to a more archaic style. The extremity of styles juxtaposed next to each other also contributes to the cartoonish feel of the piece, which is exacerbated by the exaggerated smile and slightly “wild” eyes of Enma. Kyosai, like Shohaku, is able to harness different styles of painting to suit his work, except he goes a step further in this case to combine two styles in one piece.

With such an eclectic range of styles and genres developing in the same era, it is no wonder the Edo period has been hailed as “the age of imagination” in Japanese art. In building on the rich artistic and cultural traditions of past historical periods, yet embracing more modern approaches, artists of the Edo made no small contribution to the evolution of Japanese art over the years.

Oranges and Sardines – Conversations on Abstract Painting (2009)

Details about the exhibition

Eva Hesse, H+H

Oranges and Sardines, simply put, is the product of a combined effort by six contemporary artists to showcase their thoughts and impressions of the art-making process, and provide some insight into how contemporary abstract artists in this day and age approach their medium. In the exhibition, this goal is achieved by juxtaposing one or two of each artist’s recent works with a number of previous works by other artists who have had a great impact on them. While the exhibition boasts one unifying theme – conversations on abstract painting – the works on display span a plethora of styles and philosophies, as one might expect from a group exhibition of this magnitude. Each artist brings to the table differing voices and perspectives, running the slight risk of transforming Oranges and Sardines from a subtle conversation into a full-blown group debate.

Because of this relative lack of unity across artists, I have chosen to analyze two works, both chosen by Mary Heilmann to be included in her section of the exhibition. While Heilmann’s art is surprisingly simple in form and Mondrian-esque, the pieces that influenced her in her career are much more varied. One particular work of interest is Bruce Nauman’s Untitled (1965), the only sculpture chosen by Heilmann. It consists of a metal “pipe” extending from the wall of the gallery, forming a downward parabola and ending as a horizontal bar on the floor. While it is certainly not the most stunning of visual spectacles, it pulls the viewer in, extending through the traditional “frame” in the gallery and into the viewer’s personal space. This is consistent with the post-structuralist mentality that was made popular in the 1960s, questioning the validity and neutrality of the frame in art production. Not only is Nauman challenging the physical frame of the work by invading the viewer’s space, but he could also be thought of as pushing the boundaries of the institutional frame – in this case the frame of the art gallery – as well. The sculpture conveys the impression of being a very industrial work, seemingly pre-fabricated and lacking something in the way of artistry. If one were to look at it out of context, it could very well be a machine part, or a broken portion of a bent staircase banister. This could be taken as an “institutional critique”: a re-framing of the art world’s assumptions about the institution of the art gallery and its supposed neutrality, in the vein of Robert Smithson’s A Non-site. Who is to say what is art and what is not? Traditionally, the strict rules of the art gallery might dismiss a work of this nature, but not in Nauman’s dialectic.

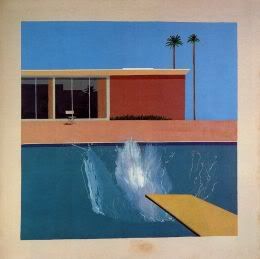

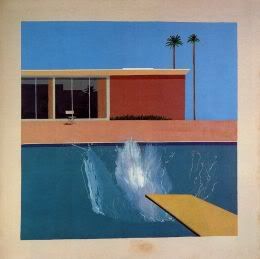

David Hockney, A Bigger Splash

A second work that also seems to hold some post-structuralist sentiments is A Bigger Splash by David Hockney (1967). If Nauman’s Untitled was an open tribute to post-structuralism, this piece is a subtle nod to it, with tongue firmly placed in cheek. The subversive element in this case lies not in the painting’s form or subject matter, but in how it was made. The painting depicts a swimming pool that someone has supposedly just jumped into, making a huge, attention-grabbing splash in the bottom half of the scene. The splash of water was “painted” onto the canvas by blowing paint through a little tube typically used for putting fixative on a drawing. Hockney was effectively painting the splash by actually making a splash, something that contradicted the classical representational nature of painting. In this way, Hockney seems to be critiquing – and, in the process, breaking – the rigid rules imposed by a previous generation of painters. Also, by using a technique as transparent as this, he is re-framing the artistic process and possibly mocking it as an institution; the overall impression one gets from this work is one of spontaneity and throwing caution to the wind, overriding obsolete rules in the face of innovation.

It is not difficult to understand why these two works have been included in Heilmann’s selection of significant influences to her development as a contemporary abstract artist. Both Kaufman’s Untitled and Hockney’s A Bigger Splash challenge one’s preconceptions of art, engrained as they are in the institutional mechanisms of the art world. Each piece is subversive and bold in its own way, and speaks to the viewer outside of its so-called “frame”. The opinions and perspectives each work brings to this exhibition – this amalgamation of conversations on abstract painting – are of no small value.

Sources

Foster, Hal, Krauss, Rosalind, Bois, Yve-Alain, and Buchloh, Benjamin H.D. Art Since 1900. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2007.

Eva Hesse, H+H

Oranges and Sardines, simply put, is the product of a combined effort by six contemporary artists to showcase their thoughts and impressions of the art-making process, and provide some insight into how contemporary abstract artists in this day and age approach their medium. In the exhibition, this goal is achieved by juxtaposing one or two of each artist’s recent works with a number of previous works by other artists who have had a great impact on them. While the exhibition boasts one unifying theme – conversations on abstract painting – the works on display span a plethora of styles and philosophies, as one might expect from a group exhibition of this magnitude. Each artist brings to the table differing voices and perspectives, running the slight risk of transforming Oranges and Sardines from a subtle conversation into a full-blown group debate.

Because of this relative lack of unity across artists, I have chosen to analyze two works, both chosen by Mary Heilmann to be included in her section of the exhibition. While Heilmann’s art is surprisingly simple in form and Mondrian-esque, the pieces that influenced her in her career are much more varied. One particular work of interest is Bruce Nauman’s Untitled (1965), the only sculpture chosen by Heilmann. It consists of a metal “pipe” extending from the wall of the gallery, forming a downward parabola and ending as a horizontal bar on the floor. While it is certainly not the most stunning of visual spectacles, it pulls the viewer in, extending through the traditional “frame” in the gallery and into the viewer’s personal space. This is consistent with the post-structuralist mentality that was made popular in the 1960s, questioning the validity and neutrality of the frame in art production. Not only is Nauman challenging the physical frame of the work by invading the viewer’s space, but he could also be thought of as pushing the boundaries of the institutional frame – in this case the frame of the art gallery – as well. The sculpture conveys the impression of being a very industrial work, seemingly pre-fabricated and lacking something in the way of artistry. If one were to look at it out of context, it could very well be a machine part, or a broken portion of a bent staircase banister. This could be taken as an “institutional critique”: a re-framing of the art world’s assumptions about the institution of the art gallery and its supposed neutrality, in the vein of Robert Smithson’s A Non-site. Who is to say what is art and what is not? Traditionally, the strict rules of the art gallery might dismiss a work of this nature, but not in Nauman’s dialectic.

David Hockney, A Bigger Splash

A second work that also seems to hold some post-structuralist sentiments is A Bigger Splash by David Hockney (1967). If Nauman’s Untitled was an open tribute to post-structuralism, this piece is a subtle nod to it, with tongue firmly placed in cheek. The subversive element in this case lies not in the painting’s form or subject matter, but in how it was made. The painting depicts a swimming pool that someone has supposedly just jumped into, making a huge, attention-grabbing splash in the bottom half of the scene. The splash of water was “painted” onto the canvas by blowing paint through a little tube typically used for putting fixative on a drawing. Hockney was effectively painting the splash by actually making a splash, something that contradicted the classical representational nature of painting. In this way, Hockney seems to be critiquing – and, in the process, breaking – the rigid rules imposed by a previous generation of painters. Also, by using a technique as transparent as this, he is re-framing the artistic process and possibly mocking it as an institution; the overall impression one gets from this work is one of spontaneity and throwing caution to the wind, overriding obsolete rules in the face of innovation.

It is not difficult to understand why these two works have been included in Heilmann’s selection of significant influences to her development as a contemporary abstract artist. Both Kaufman’s Untitled and Hockney’s A Bigger Splash challenge one’s preconceptions of art, engrained as they are in the institutional mechanisms of the art world. Each piece is subversive and bold in its own way, and speaks to the viewer outside of its so-called “frame”. The opinions and perspectives each work brings to this exhibition – this amalgamation of conversations on abstract painting – are of no small value.

Sources

Foster, Hal, Krauss, Rosalind, Bois, Yve-Alain, and Buchloh, Benjamin H.D. Art Since 1900. New York: Thames and Hudson, 2007.

Nathalie Djurberg (2009)

Details about the exhibition

It's the Mother

Nathalie Djurberg’s ongoing exhibition at the Hammer Museum is one that is strangely dissonant. The very nature of her medium – short claymation films filled with bright, candied colors and cartoon-like figures – evokes impressions of child-friendly productions in the vein of Wallace & Gromit and Gumby. In fact, the three clips in this exhibition begin in such a fashion: innocent, easy on the eyes, and without a hint of anything portentous to come. However, these illusions are quickly pushed aside as each work quickly progresses into a portrait of the grotesque and macabre, oft through a strange, dream-like process. Djurberg is definitely no stranger to the expression of the primal, and motifs of pregnancy, lust and fear make their appearances throughout the exhibition. She also focuses a great deal on the interactions between children and parents in two of her works, while in her third work, adult figures seem to disappear completely. This seeming obsession with primitivism, childhood, and parent-child bonds hints of a Freudian aspect to her work. As such, examining her work through the lens of Psychoanalysis might serve to give us more insight into what lies behind it.

In It’s the Mother, a mother plays with a group of her children: all girls save one boy. The children are hyperactive and harangue their tired and worn-out mother to no end. One child approaches the mother’s genitals – perhaps hinting at the genital phase of Freudian psychosexual development – and starts to worm her way into her vaginal orifice, in a sort of “reverse birthing” process. The mother bloats up and is obviously in pain, but does nothing to stop her. The other children follow suit, one by one, in agonizing succession. Meanwhile the mother weeps, huge tears streaming down her body, while the remaining children comfort her and push down the protrusions that are beginning to form on her body. The boy goes in the last, but not after stroking her rather sensually. When all the children are inside, body parts start sprouting from the mother’s body and she metamorphosizes into a monstrous figure, struggling to maintain her balance.

This work is an intriguing play on parent-child relationships, and also an acknowledgement of the frightening, even insane things that children can be capable of. One is reminded of Freud’s belief that we are born with the “aggressive instinct”, which “already shows itself in the nursery” and reigned in primitive times. Even though the children show affection by comforting their mother, aggression seems to overcome their love as they still cause her pain in the end by re-entering her womb. Furthermore, the one son who is left seems to desire her sexually, hinting at some Oedipal attraction buried under the guise of comfort. In the end, we see that the mother has resigned herself to an unhappy fate just for her children; she is the one who suffers most from the parent-child bond. This just serves to illustrate the powerlessness of the mother figure in a patriarchical society, and the degree of her sacrifice for the sake of her children.