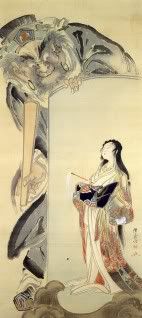

Kawanabe Kyosai, The King of Hell with a Courtesan

The Age of Imagination: Japanese Art, 1615 - 1868 is a visionary exhibition that allows the viewer a valuable glimpse into the art of Japan’s Edo period. The collection of paintings on display consists of a myriad of diverse styles, philosophies and subject matter – fitting indeed for the theme of creative progression that is characteristic of the Edo period. The exhibition encompasses many aspects of traditional Japanese art: religious depictions, genre paintings, and landscapes all make their appearances through an array of forms and mediums. The viewer is able to emerge from his experience satisfied in the knowledge that he has seen a comprehensive and fair representation of Edo-era painting.

In order to capture the holistic nature of The Age of Imagination, I have selected several pieces ranging across an eclectic mix of artists and styles to write about. A work that caught my eye early on in the exhibition is The Death of the Buddha by Nakamichi Sadasue (c. 18th century), a hanging scroll painted with ink and colors on paper. The scroll depicts a Buddha – presumably Shaka – in the process of entering nirvana, surrounded by disciples, other deities and animals. His mother, Queen Maya, also makes an appearance in the top right corner, descending from the heavens with an entourage behind her. It was interesting to note that this painting has much in common with Nirvana of the Buddha (c. 711) at the Horyuji Pagoda, which is a depiction scene of the death of Shaka using the medium of clay sculptures. Both works share very similar layouts, with the Buddha figure reclining on a pedestal in the center of the tableau, surrounded by his consorts, and Maya at the corner. Furthermore, like its predecessor from the Nara period, Sadasue’s work shows some obvious iconographical traits. Firstly, there is a clear distinction between the appearances of the disciples (Hinayana) and the bodhisattvas (Mahayana): the disciples form a weeping, bedraggled lot, evidence of their incomplete mastery of the Buddha’s instruction, while the bodhisattvas look on impassively, understanding that death is but a means to an end for the Buddha. Secondly, a golden skin tone marks the Buddha and bodhisattvas as divine beings. (However, in the case of the Horyuji sculptures, only Shaka is imbued with the golden skin). Of course, there are certain aspects to Sadasue’s painting that set it apart from the Horyuji tableau and give it a slightly more modern quality. Decorative elements are emphasized over realism – clouds, trees and water are painted with an abstract flair – and the artist plays with size and perspective – the Buddha is very large in comparison to everyone else, perhaps to emphasize his presence, while Maya seems shrunken down to show that she is further away.

Another work of interest is Soga Shohaku’s Wild Horses (c. 18th century), a pair of six folding screens, done with ink and gold on paper. This painting has a surprisingly impressionistic quality to it. Several horses are painted in different positions and poses across the screens, the dynamism of their movements exaggerated through varied, almost haphazard brushwork. Traditional attention to detail and refined line work are substituted in favor of bold, thick strokes. Also worth noting is Shohaku’s use of empty space in the work. The lack of any background elements in the painting serves to focus the viewer’s attention solely on the horses; indeed, the energy emanating from the subjects is more than sufficient to draw the viewer in and hold his interest. The dynamism inherent in the painting, as well as the artist’s effective use of blank space to further enhance it, seems reminiscent of another Edo period painting in the decorative tradition: Wind and Thunder Gods by Sotatsu.

However, Wild Horses offers but a small glimpse of Shohaku’s artistic versatility. In another of his paintings showcased in the same exhibition, Mount Fuji and Seiken-ji Temple at Miho (c. 18th century), Shohaku uses a completely different style, appropriate to the subject matter. Unlike the relatively abstract, almost careless brush techniques used in Wild Horses to bring out the uncontained energy of the horses, Shohaku uses a more archaic painting style to depict the Mount Fuji and its surroundings in all its age and grandeur. This does not in fact signal an evolution in painting style, but an ability to adapt different styles to fit different themes. Mount Fuji and Seiken-ji Temple at Miho leans more toward realism and boasts a refined painting style, with straightforward use of perspective and high visual accuracy. The only thing one can find in common with Wild Horses is Shohaku’s use of blank, flat space, this time used to give the impression of distance. The foreground of the painting is more detailed and strongly rendered with shading, while the background gets gradually lighter and more washed out, till Mount Fuji is simply a white shape against the sky.

The King of Hell with a Courtesan (c. 19th century) by Kawanabe Kyosai – a hanging scroll with ink and colors on silk – is a refreshingly humorous piece, fitting with the caricatural tone of many of his other works. In it, Enma the king of hell, dressed as a Chinese judge, is gazing with ill-contained delight at the courtesan of hell, Jigoku Dayu, in a mirror. What drew my interest were the contrasting styles of painting used within the work itself. The king, being a large, burly figure lacking in subtlety, is painted quite roughly, using thick coarse brushstrokes. The courtesan, who has much smaller proportions, is finely painted; her hair, facial features and kimono convey a sense of delicacy. One could go further to observe that painting style used for Enma is given a more modern treatment than the understated lines of the courtesan, which could be seen as faithful to a more archaic style. The extremity of styles juxtaposed next to each other also contributes to the cartoonish feel of the piece, which is exacerbated by the exaggerated smile and slightly “wild” eyes of Enma. Kyosai, like Shohaku, is able to harness different styles of painting to suit his work, except he goes a step further in this case to combine two styles in one piece.

With such an eclectic range of styles and genres developing in the same era, it is no wonder the Edo period has been hailed as “the age of imagination” in Japanese art. In building on the rich artistic and cultural traditions of past historical periods, yet embracing more modern approaches, artists of the Edo made no small contribution to the evolution of Japanese art over the years.

No comments:

Post a Comment